“Did you hear about the border war between Texas and Oklahoma? The Oklahomans were throwing dynamite across the border at the Texans. The Texans were lighting it and throwing it back!”

And not to show favoritism, here’s this one…

Q: How many University of Texas freshmen does it take to change a light bulb?

A: None, it’s a sophomore course.

Like many states that border each other, Texas and Oklahoma have developed an interesting relationship that some have described as a sibling rivalry. They will prod and poke each other and get on each other’s nerves, but mess with one and the other comes running. This was the case in 2013 when tornadoes destroyed homes in southern Oklahoma. Hundreds of Texans poured across the border to help out.

When you talk about Texas/Oklahoma rivalry, it usually has something to do with the friendly football rivalry between the Sooners of the University of Oklahoma in Norman and the Longhorns of the University of Texas at Austin. But the friction between the two neighbors hasn’t always been friendly, such as the time in 1930 when Oklahoma and Texas came close to shooting it out with each other in the Red River Bridge War.

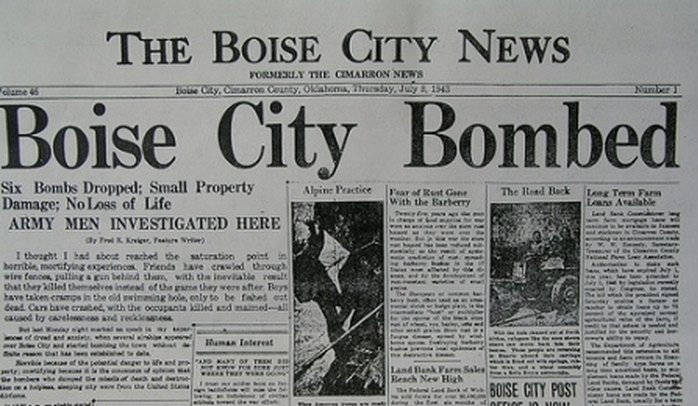

And then there was the time just past midnight on July 5, 1943, when Texas bombed Oklahoma…

In the late evening hours of July 4, 1943, a B-17 Flying Fortress and her ten-man crew took off from the U.S. Army Airforce base in Dalhart, Texas, located in the northwest corner of the Texas panhandle. The Dalhart base was a major training facility for Air Force bomber crews, and this crew was on a training mission. Its objective was a bombing range located twenty miles northeast of Dalhart near Conlen, Texas. This was a night-time bombing mission so the crew was told that they could spot their target by looking for a square area illuminated on each of its four corners with lights.

What happened within the next hour was described by Major C. E. Lancaster, commanding officer of the Dalhart base, as an accident caused by “a mistake of navigation.” Somehow, the B-17 crew flew straight north rather than northeast, and no one seemed to notice that they had flown twice as long as they were supposed to.

Shortly past midnight on July 5th, the crew spotted what they believed was their target – a square area illuminated on its corners with lights. What they were really seeing was not their target on the bombing range in Conlen, Texas, but the lights in the courthouse square in Boise City, Oklahoma.

The B-17 circled to begin the first of six passes over their target – dropping one bomb with each pass. Fortunately, the one-hundred-pound bombs were practice bombs that were filled with sand and only contained three pounds of gun powder.

The first bomb blew the door off of an empty garage and left a 20-by-40-inch crater. The second bomb blew the door off of the First Baptist Church and busted some of the stained-glass windows. It also left a three-foot deep crater which became quite an attraction, prompting the pastor of the church to remark that if even a quarter of the people who came to see the crater would attend church, he would be a success. The rest of the bombs hit near a downtown shop, a boarding house missing a parked tanker truck full of fuel, a private residence, and the railroad tracks on the edge of town. The crew would have made yet another pass over their target, had not Frank Garrett, an employee of the city’s power company, pulled the master switch for the town’s power. The crew saw the lights go out and interpreted it to mean that their exercise was over, so they headed back to Dalhart. No one was injured during the attack and the total cost of the damage was around twenty-five dollars.

The B-17 crew, which was extremely embarrassed by the incident, was given a choice of either disciplinary action or immediate transfer to the European theater of war. They chose the latter, and eventually became one of the top B-17 bombing crews in the Eighth Air Force. They served with distinction and only one year after bombing Boise City, the same crew led an eight-hundred plane bombing mission over Berlin, Germany.

After learning the truth about the attack, the citizens of Boise City soon got over any bad feelings. It became a source of pride for the citizens of Boise because it focused national attention on their little burg. Time and Newsweek both printed stories about the attack. Time magazine joked that the citizens of Boise did what any other citizen would do when being bombed; “Most of them ran like hell, in no particular direction.” The proud citizens of Boise even held the distinction of being the only city in the continental United States to be bombed during WWII.

Fifty years after the attack, Boise City erected a bronze plaque near a bomb crater with a replica bomb protruding out of it as a memorial to the night that they were bombed by Texas.